The Science Rabbit Newsletter | Professor Andrew Bubak

In August 2025, a study in JAMA Neurology showed that children exposed to the pesticide chlorpyrifos before birth had visible brain abnormalities on MRI scans; altered cortical thickness, damaged nerve insulation, reduced blood flow (1). These weren’t subtle statistical blips. They were structural changes in 270 children followed from birth through adolescence.

Meanwhile, that same pesticide remains legal on American farms and golf courses after regulatory whiplash; banned in 2021, unbanned after industry lawsuits, partially restricted in 2025. The children in the study weren’t farmworkers’ kids. Their mothers were exposed when their New York City apartments were fumigated. Indoor use was banned in 2001. Agricultural and other uses continue.

The evidence against pesticides have accumulated for three decades. The pattern is unmistakable: these compounds cross the blood-brain barrier, disrupt neurotransmitter systems, trigger inflammation, and leave lasting fingerprints on brain structure. The developing brain is exquisitely vulnerable. And we keep debating “acceptable risk” while a generation of children, particularly in agricultural communities, serves as an uncontrolled experiment.

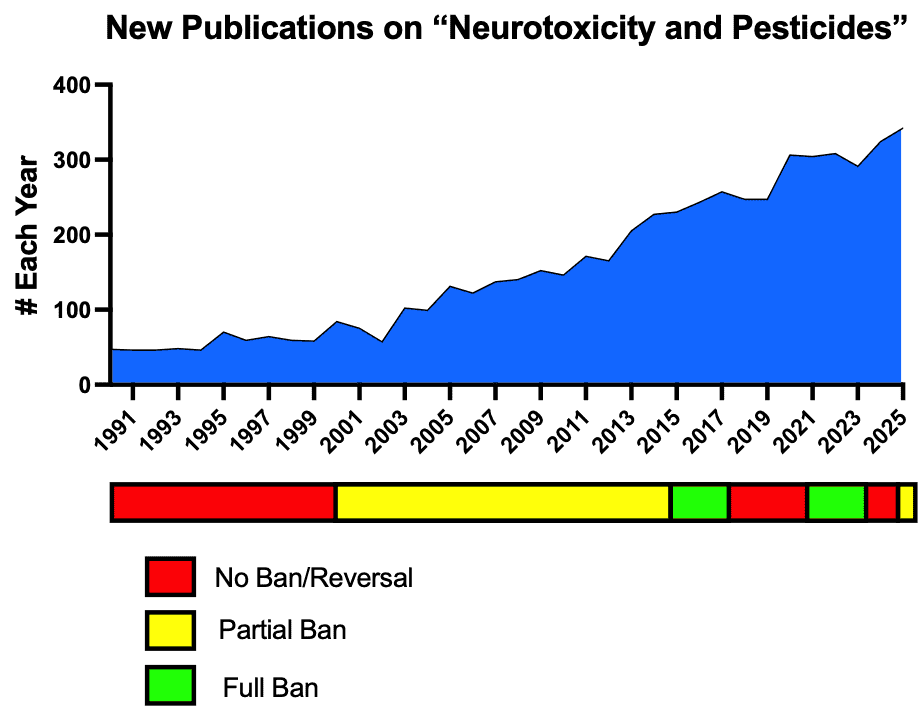

(Figure: The number of peer-reviewed publications investigating Neurotoxicity and pesticides (NCBI Index) has steadily increased over 3 decades yet we have seen discordant regulations.)

The IQ Studies That Should Have Changed Everything

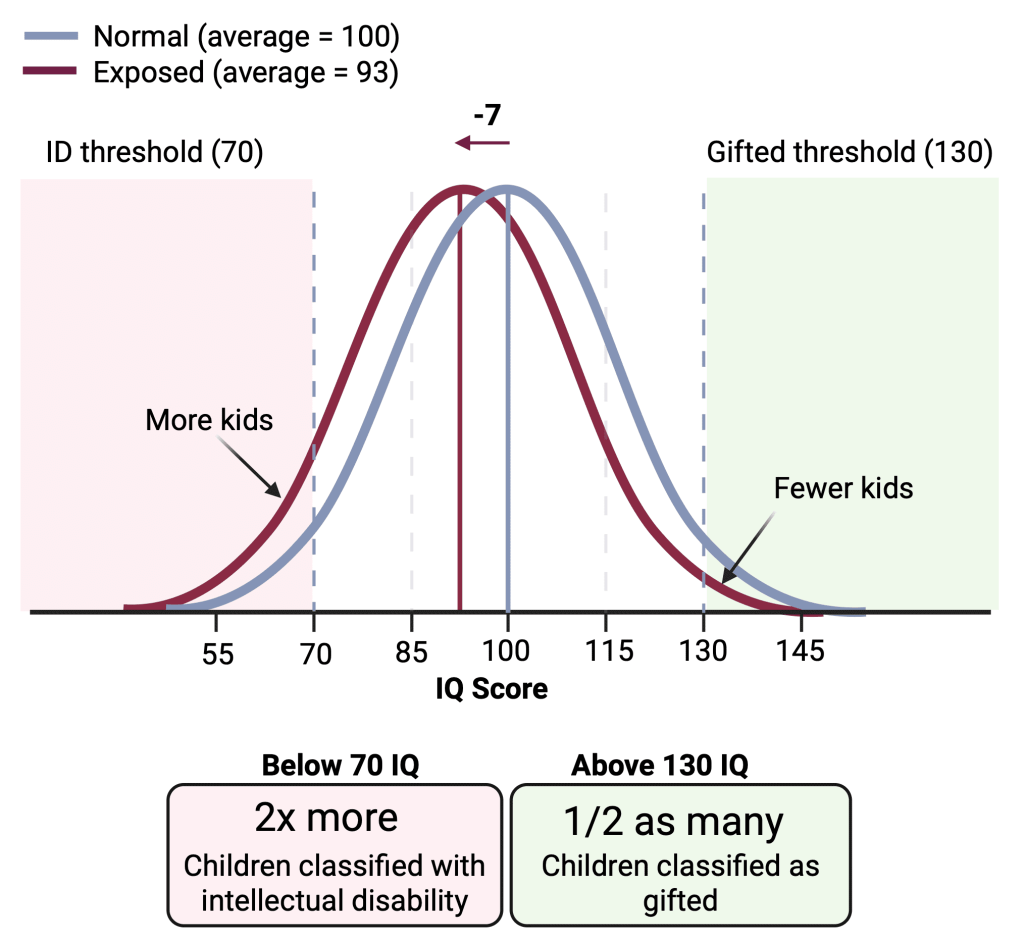

A study in 2011 followed pregnant women and their children from a predominantly agricultural community in California for years, measuring pesticide exposure and tracking cognitive development. The most striking finding was that prenatal organophosphate exposure at typical environmental levels was associated with IQ reductions of 5.5 to 7 points (2).

A 7-point drop might sound modest. It’s not. At the population level, it doubles the number of children classified as intellectually disabled while reducing the number classified as gifted by half (3). They found that for every increase in exposure there was an increase in detrimental impacts, and for every decrease, a corresponding decrease in effect. There appeared to be no safe threshold of exposure. This is not a fringe study, other independent studies have showed similar effects.

(Figure: A shift of -7 IQ points doubles the number of children classified with intellectual disability and reduces the number of children classified as gifted by half. Graph made with Biorender.)

What Pesticides Actually Do to the Developing Brain

Organophosphates, including chlorpyrifos, malathion, and diazinon, were originally developed as nerve agents in World War II. Their mechanism is devastating; they inhibit acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme that breaks down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (4).

In acute poisoning, this causes a cholinergic crisis; seizures, muscle twitching, potentially death. But the developing brain faces something different. Acetylcholine isn’t just a neurotransmitter in mature brains. During development, it guides the migration and connectivity of neurons (5). Disrupting this signaling during critical windows doesn’t cause immediate symptoms. It causes lasting alterations in brain architecture.

The 2025 study captured these alterations directly (1):

- Thickened cortex (sounds good, but indicates disrupted neural pruning)

- Abnormal white matter tracts in motor and communication pathways

- Compromised myelin (the insulation that enables rapid neural signaling)

- Reduced blood flow to motor regions

- Impaired neuronal metabolism brain-wide

Children with higher exposure performed worse on motor coordination tests. The structural changes predicted the functional deficits.

The Glyphosate Question

Glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup and the world’s most-used herbicide, was long considered safer for the brain because it supposedly didn’t cross the blood-brain barrier. Recent research has demolished this assumption.

A 2022 study demonstrated that glyphosate does cross into brain tissue in mice, accumulating in a dose-dependent manner (6). At higher doses, it increased blood-brain barrier permeability itself, potentially creating a self-amplifying cycle of infiltration.

More troubling: a December 2024 study found that glyphosate-induced neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s-like pathology persisted for six months after exposure ended (7). The brain’s typical resilience appears insufficient to overcome the damage.

One study found glyphosate detectable in 99.8% of the French population (8). Read that sentence again, seriously. We’re all exposed. Whether current levels cause clinically meaningful effects in humans remains uncertain, but the animal data and epidemiological data is increasingly alarming.

The Parkinson’s Connection

The link between pesticides and Parkinson’s disease is one of the most robust findings in environmental neuroscience. A 2024 meta-analysis confirmed what epidemiological studies have shown for decades: pesticide exposure significantly increases Parkinson’s risk, with organophosphates and organochlorines showing the strongest associations (9).

The mechanism makes sense: pesticides cause oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and protein aggregation, the same pathways disrupted in Parkinson’s. A July 2025 study found that pesticide exposure triggers alterations in brain gene activity through epigenetic processes that can potentially persist after exposure ends (10). Environmental toxins may be priming brains for disease years before symptoms appear.

The most insane thing is that neuroscientists, like myself, use certain pesticides like rotenone (which is also used to control nuisance fish populations) to induce Parkinson’s disease pathology in rodents so we can study the disease! It is a well-established method that induces the same motor and non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s in rats. That is not correlation, that is direct causation.

Household pesticides matter too. High household use was associated with nearly double the odds of developing Parkinson’s (11). This isn’t just a farmworker issue, though farmworkers and agricultural communities bear the greatest burden.

Why Regulation Has Failed

The chlorpyrifos saga is a case study in regulatory frustration influenced by corporate profits:

2000: EPA bans residential use over child safety concerns

2015: EPA proposes banning agricultural use

2017: Trump administration reverses course

2021: Federal court orders food ban; EPA complies

2024: Different court sides with industry; ban reversed

2025: Partial restrictions; still legal on 11 crops (alfalfa, apple, asparagus, cherry, citrus, cotton, peach, soybean, strawberry, sugar beets, and wheat.

Throughout this, the science only got stronger. The gap between evidence and action reflects a structural problem: companies profiting from pesticides fund the safety studies submitted for approval. A 2018 analysis found that industry-funded developmental neurotoxicity studies concluded “no effects” at doses where independent studies found cognitive impairments (12). The methodology in industry studies was designed to minimize detection of harm.

A common justification for wide-spread pesticide/herbicide use I hear is that “Americans will starve due to loss of crops”. The math doesn’t support this. Specifically, Americans throw away about 38% of food produced and the average reduction in crop yield in organic farms is about 20%. We could eliminate neurotoxic pesticides and still have 18% leftover to throw away.

What Actually Needs to Happen

I’m wary of placing systemic failures on individual consumers. But for those wanting to reduce exposure, especially during pregnancy:

- Organic produce for the “Dirty Dozen” reduces urinary organophosphate metabolites by ~70% (13)

- Wash and peel conventional produce (helps, but doesn’t eliminate absorbed pesticides)

- Use integrated pest management instead of chemical sprays at home

- Remove shoes at the door if living near agricultural areas

- Filter your drinking water and water you use to boil food

But the real solutions are structural:

- Full ban on chlorpyrifos and similar organophosphates with proven developmental neurotoxicity

- Reformed testing requirements that don’t let manufacturers design their own safety studies

- Environmental justice protections for communities bearing the highest exposure burden

The Bottom Line

The evidence that pesticides damage developing brains isn’t speculative. It’s visible on MRI scans, measured in IQ points, and reflected in rising rates of neurodevelopmental disorders. The mechanisms are understood. The vulnerable populations are identified. What’s lacking isn’t scientific understanding. It’s political and social will.

The children in that 2025 study didn’t choose their exposure. Neither did the farmworker children in California’s Salinas Valley. The developing brain’s vulnerability to environmental neurotoxicants isn’t a partisan issue. It’s a matter of whose children we’re willing to sacrifice for agricultural efficiency.

We know enough to act. The question is whether we will.

Stay Curious,

Andrew

References

- Peterson BS, et al. Brain Abnormalities in Children Exposed Prenatally to the Pesticide Chlorpyrifos. JAMA Neurology. 2025;82(10):1057-1068.

- Bouchard MF, et al. Prenatal Exposure to Organophosphate Pesticides and IQ in 7-Year-Old Children. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2011;119(8):1189-1195.

- Bellinger DC. A Strategy for Comparing the Contributions of Environmental Chemicals and Other Risk Factors to Neurodevelopment of Children. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012;120(4):501-507.

- Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M. The susceptibility of humans to neurodegenerative and neurodevelopmental toxicities caused by organophosphorus pesticides. Archives of Toxicology. 2023;97(12):3037-3060.

- Slotkin TA. Cholinergic systems in brain development and disruption by neurotoxicants. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2004;198(2):132-151.

- Winstone JK, et al. Glyphosate infiltrates the brain and increases pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2022;19:193.

- Bartholomew SK, et al. Glyphosate exposure exacerbates neuroinflammation and Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology despite a 6-month recovery period in mice. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:306.

- Grau D, et al. Quantifiable urine glyphosate levels detected in 99% of the French population. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2022;29:32882-32893.

- Samareh A, et al. Pesticide Exposure and Its Association with Parkinson’s Disease: A Case-Control Analysis. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology. 2024;44:73.

- Tsalenchuk, M., Farmer, K., Castro, S. et al. Unique nigral and cortical pathways implicated by epigenomic and transcriptional analyses in rotenone Parkinson’s model. npj Parkinsons Dis. 11, 217. 2025.

- Santos-Lobato BL, et al. Household herbicide use and Parkinson’s disease risk. Journal of Neural Transmission. 2025.

- Mie A, et al. Safety of Safety Evaluation of Pesticides: developmental neurotoxicity of chlorpyrifos. Environmental Health. 2018;17:77.

- Hyland C, et al. Organic diet intervention significantly reduces urinary pesticide levels. Environmental Research. 2019;171:568-575.

Leave a Reply